A STROKE OF GENIUS

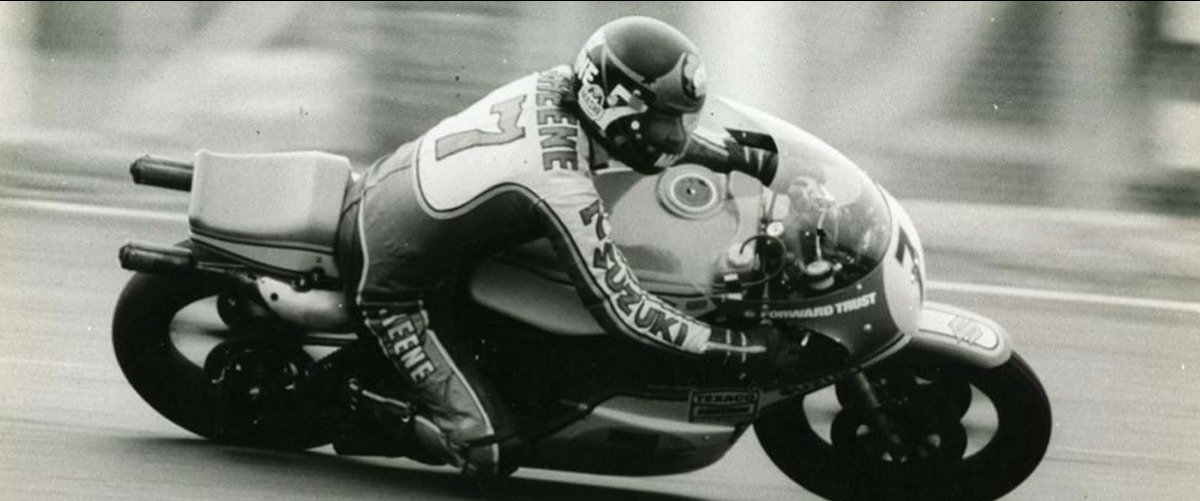

Over 40 years ago Suzuki changed the face of 500cc GP racing with the release of the two-stroke square four XR14. This, and subsequently the legendary customer RG500 went on to win seven consecutive 500GP championships, four rider world titles, and allowed privateers to compete for GP glory on an equal footing with factory teams for the first time. One of the men responsible for this machine was Makoto ‘Big Mac’ Suzuki who, alongside Makoto Hase, developed and built the RG500 that in 1976, with Barry Sheene onboard, delivered Suzuki its first 500GP world title.

In the early 1970s, the thought of entering 500GPs with a two-stroke motor was laughable. ‘Smokers’ were confined to the tiddler classes. However despite all this, in 1974 Suzuki went against convention and entered the championship using a 500cc two-stroke that would go on to dominate the world.

“People thought we were crazy as two-stroke engines were only used on small bikes, but that was all Suzuki knew, we didn’t build four-strokes,” remembers Makoto Suzuki. “The decision was made for us, we had no option so we looked at our small capacity bikes. We had already built square four and V4 125cc and 250cc race bikes, so we upsized them. We started the project in 1973 with the target of being ready for the 1974 season and only had four people were working on it – two for the engine and two for the chassis.”

Although nowadays GP racing has reverted to four-stroke, the bike that Suzuki built demonstrated that two-strokes are very good at producing power. While this was good news for the engine’s development team, the chassis engineers were faced with some tough challenges.

“With the bike we aimed for over 100bhp, but it made 110bhp in the end,” said Makoto Suzuki, “which would have been an issue for the chassis had we not been racing the XR11 in America. The XR11 was a 750cc triple with lots of power so we had all the chassis issues with this bike. In America we suffered torn tyres, snapped drive chains, overwhelmed suspension, it was terrible, the chassis development was so far behind the engine.

“For the RG500 we used the knowledge from the XR11 to build a good chassis, however the engine was very hard to ride and peaky. The power was produced from 8,000 – 10,500rpm, that was it, but the GP mechanics at the circuit could alter these characteristics with exhausts and jets at the circuits. At that time there was a lot of experimentation and development happening, we were looking for inspiration from everywhere, even household items.

“The original exhaust end cans on the RG500 were modified green tea cans, they looked the correct size so I introduced this technology into the GP bike.”

Success was quick to arrive for the RG500 and in its debut year Barry Sheene rode the XR14 to its, and Suzuki’s, first 500GP win at the Assen. Two years later he brought Suzuki its first 500GP world title, however for the RG’s development team, it was the constructor’s title that came alongside the rider’s title that meant the most.

“For Suzuki the most important thing was the constructor’s championship, not the rider’s one. If your rider wins you can only say the rider is a world champion, if you win the constructor’s championship you can say ‘Suzuki is world champion’. This drove Barry mad, he would get very upset because the privateer bikes were identical to the factory ones! For Suzuki it was excellent, we won seven constructor’s championships in a row,” laughs Makoto Suzuki.

With the RG500 Suzuki made a radical decision – they would release a privateer bike at a cost of £12,000 each that were identical in specification to the factory machines. With a grid full of RGs, the constructor’s title was all but assured.

“The only difference was the fact the factory bikes had titanium or magnesium fasteners where the production bike had steel or aluminium ones. The engine was 100% identical, we just changed the name from prototype to production. You could buy a production RG500 and win a GP, as Jack Middleburg did in 1981. That was the last time a privateer won a 500GP, however he rode an RG500 Mk VIII based on the XR22. You can imagine Barry Sheene’s frustrations.”

With the 1976 and 1977 titles in the bag thanks to Barry Sheene, 1978 saw Suzuki face tough competition, and upgraded the XR14 to the XR22 with its ‘step motor’. This engine used the first ‘cassette gearbox’ on a motorcycle, a feature that is common to most engine designs nowadays but was radical technology in 1978, designed following input from the McLaren F1 racing team. However, it was developed back in 1976, but it didn’t see the light of day until 1978.

“Barry won the 1976 title on the XR14 but we held the XR22 back in 1977 in case other manufacturers came out with something special,” explains Makoto Suzuki. “Yamaha in particular were a concern, but only unveiled exhaust valves and so we kept it hidden until 1978. Also, our customer RG500 was proving very popular and we didn’t want to detract from it, although we also needed to beat it as privateer riders were starting to challenge the factory ones.

“People had developed their XR14s so well they were incredibly fast and more than capable of matching the XR22. The power was not so different with the XR22 when compared to the XR14, they both made around 124bhp, however the engine was lighter which made the bikes handle better. Weight was a big factor in GPs in the 1970s and 1980s as despite there being a minimum weight of 100kg the bikes would never match this, the best we got was 108kg. With 124bhp and 108kg, the XR22 was quite a beast!”

After developing the XR14 and subsequently the XR22, Makoto Suzuki was eventually able experience the power first hand.

“I rode the XR22 for half a lap in Japan and only once – that was enough for me. I pulled out of the pits and rode around a 200-degree corner and the rev counter wasn’t even registering as it started at 5,000rpm. On the straight I opened the throttle, the revs suddenly appeared, the bike wheelied and I pulled in. It was terrifying. I really appreciated the skill riders such as Barry Sheene had”

The square four design went on to dominate 500GP racing, taking two more world titles (1981 with Marco Lucchinelli and 1982 with Franco Uncini) and winning a total of 50 races alongside the seven consecutive constructor’s championships. But everything has to come to an end and in 1987 the square four RG500 was replaced by the V4 RGV500, something that was inevitable due to the fact the competition were all now using two-stroke motors.

“The square four had very good weight distribution and a lot of power. It is a simple engine but one that was reliable and worked very well, however it was limited in its power output, which is why it was replaced by the V4,” explains Makoto Suzuki. “The inlet port was limited in space, however on a V4 it is not. The more fuel and air you can get into an engine the more power you get out, which is why the introduction of the V4 boosted power from 133bhp to over 145bhp instantly.”

Suzuki GB recently restored Barry Sheene's world championship-winning XR14s to their former glory. Watch the two-part video documentary below.

DESIGNING THE SUZUKI' FATMILE'

The Bandit 1250-based 'FatMile' was designed using what the Japanese call Senpai-Kohei, where a young designer with new and fresh ideas is brought together to work with an experienced designer who will guide and direct them. For the FatMile designer Daniel Händler teamed up with legendary Suzuki designer Hans A. Muth, architect of the iconic Suzuki Katana.

The bike was initially built for the Glemseck 101 festival in Germany; one of the biggest café racer gatherings in Europe. Since then it has done the rounds at Intermot, EICMA and Motorcycle Live.

To stay true to the Senpai-Kohei design principle, Suzuki deliberately opted to buck the obvious trend of working with a big design studio or well-known customiser, instead putting its faith in Händler to steer the project with Muth overseeing the process.

“Of course we took a certain risk with this decision,” admits Gerald Steinmann of Suzuki Europe. “When you hire an established design agency or world-famous custom builder hardly anyone will come out with criticism. But we consciously took this different approach and chose a solution in the Japanese tradition. Looking at the FatMile now I am convinced we did the right thing.”

A number of donor bikes were considered for the project, with the Bandit 1250 eventually becoming the starting point.

“We looked at a number of options,” Händler explains. “But, along with the GSX-R, the Bandit series is an iconic series for Suzuki, so this is why we chose it.”

With Händler bringing the innovation and fresh approach, responsibility fell to Muth to guide him on his ideas, designs, concepts and finally implementation when it came to building the FatMile. Muth also had an eye on preserving the Suzuki design identity.

Händler continued, “In this project Mr. Muth was an extremely good tutor for me. At the beginning of our cooperation we shut ourselves away for three days to only talk and outline the FatMile project. That was enormously motivating and instructive for me.”

Muth added, “Mr. Händler is full of good thoughts and ideas. Sometimes I had to remind him to consider the limits of real implementation at early draft stages, but we worked in good harmony. I think that together we have created a very good machine.”

The Suzuki FatMile uses the 1255cc motor from the Bandit mated to custom Cobra Urban Killer exhausts. Swingarm is standard Bandit but the frame has a modified rear subframe and seat unit with a custom seat to go with the new Paaschburg & Wunderlich headlight, GFK front fender and custom paint scheme.

Front forks are 2012-2016 GSX-R1000 which, at 5cm shorter than Bandit forks lower the front end of the bike. Front brake calipers are Brembo monobloc from the same GSX-R1000 with GSX-R discs too. Rear stopping power comes from a four-pot Nissin caliper and B-King disc. The bike is fitted with Spiegler brake lines.

Tacho is a tiny Motogadget Motoscope and PVM wheels don Metzeler Sportec tyres. Rearsets are Rizoma RRC, handlebars are Rizoma Lux, and mirrors are Rizoma Spy-R 80.

Photography:Sven Wedemeyer